High Street Rebooted 2021

What 1,000 consumers want from the future of the high street

When RWRC launched High Street Rebooted in 2019, local shops were on their knees. The report – which outlined strategies designed to breathe new life into ailing town centres, backed by exclusive consumer research – showed that at the time a not insignificant 12% of people believed the high street as we know it would disappear altogether by 2021.

Since then the pandemic has resulted in scores of store closures, piling more pressure on physical retail. A net decline of 6,001 shops was recorded in the first half of 2020, compared with 3,509 in the same period of 2019, according to research from PwC.

Yet the changes to consumer behaviour brought about by the coronavirus crisis could in fact present the biggest opportunity in a generation to breathe new life into local high streets when customers begin to return in greater numbers.

When city centres are effectively shut down, as they have been on and off for almost a year, localism has been thriving, with people working from home seeking out their nearest high street. However, even these destinations have had many stores closed, so it is little surprise our data reveals even they have seen a decrease in footfall.

So how can the retail ecosystem – with the help of central and local government, and the community – capitalise on the fact consumers have rediscovered local high streets? After all, with many businesses signalling at-home working will continue in some form indefinitely, these are the places consumers will continue to frequent post-pandemic. So the opportunity is ripe.

The answers lie in understanding the new needs of consumers, what they really want from their high streets and the longer-term impacts of coronavirus on shopping trends.

High Street Rebooted 2021 includes exclusive findings from research with 1,000 consumers to compare how attitudes have changed since we first ran this report in 2019. You will also hear from leaders at retailers including Spar UK, Majestic Wine and Superdry.

This report will provide the strategic blueprint to identifying the new role of the high street and help retailers save their underperforming stores.

METHODOLOGY

RWRC conducted research with 1,000 UK consumers across a range of demographics in December 2020, assessing attitudes and behaviours to local high streets.

Five winning strategies

Retail Week has determined the five key strategies all retailers should focus on in 2021 and beyond in order to succeed in a market transformed by technology and shifting consumer attitudes.

| Winning strategies in this report | ||

|---|---|---|

|

|

Brand relevance and evolution | ✔ |

|

|

Agility and partnerships | ✔ |

|

|

CX | ✔ |

|

|

Innovation and investment | ✔ |

|

|

Culture and purpose | |

Chapter 1

The clock is ticking

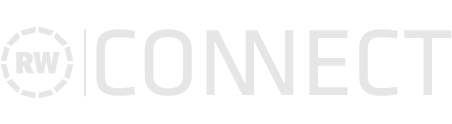

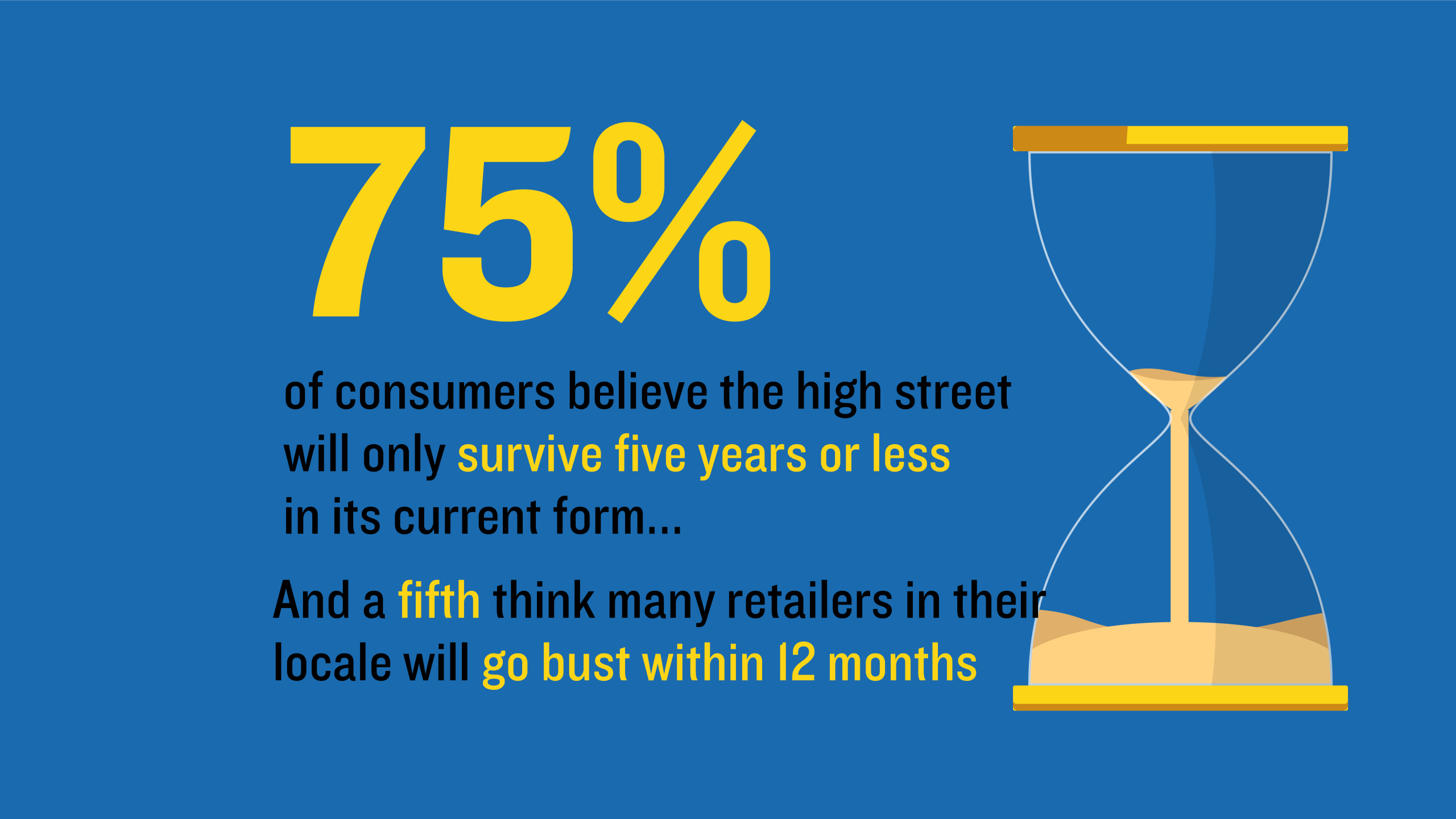

The high street will survive in its current form for just five years at best; that is the grim assessment of three quarters of 1,000 UK consumers surveyed by RWRC in December 2020, with 19% predicting many retail businesses in their locale will go bust within 12 months.

The pandemic will be to blame for much change and collapse, but long-term challenges including rising business rates, under-investment in retail premises, and consumers’ growing interest in digital and out-of-town shopping all play their part.

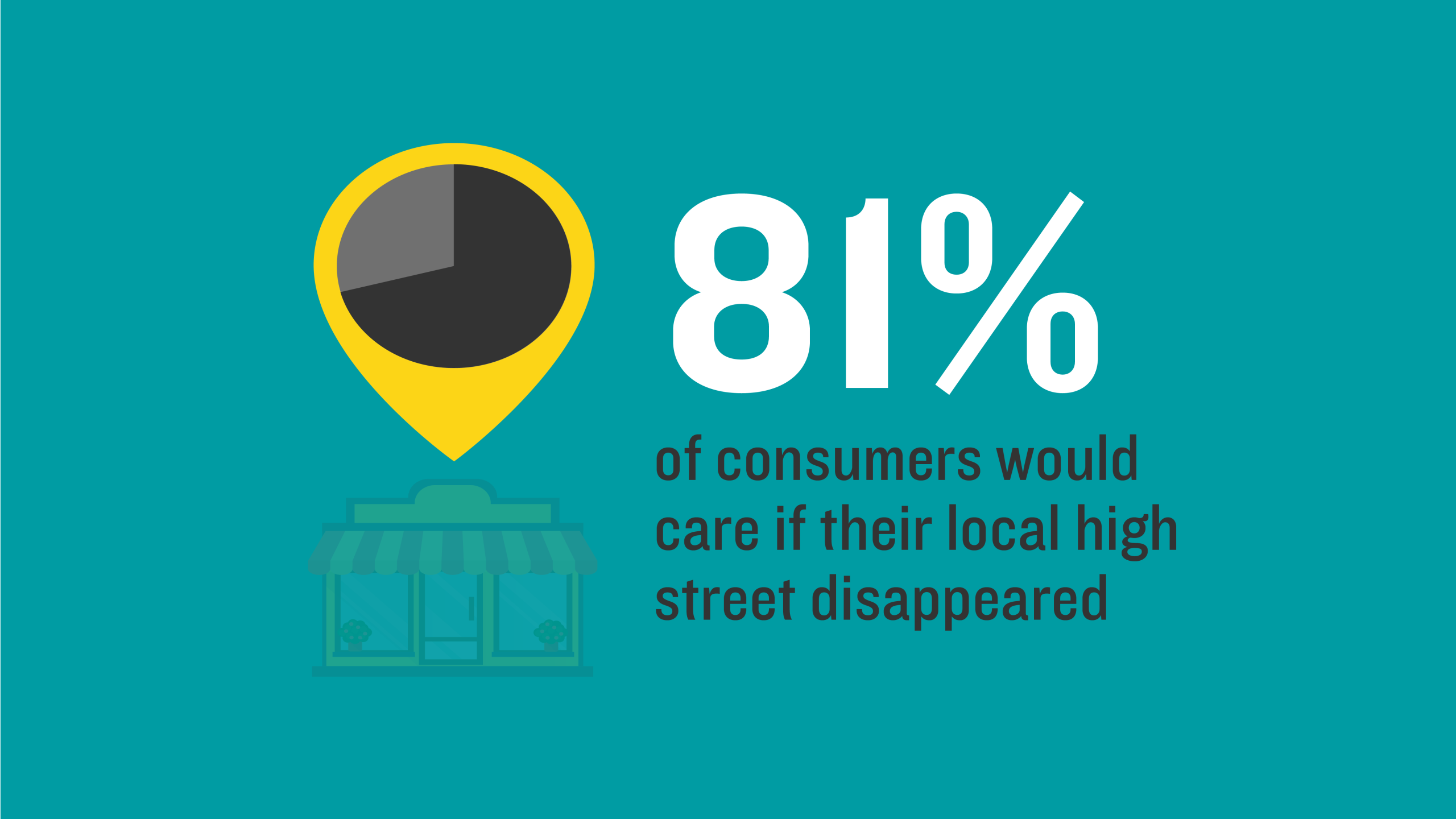

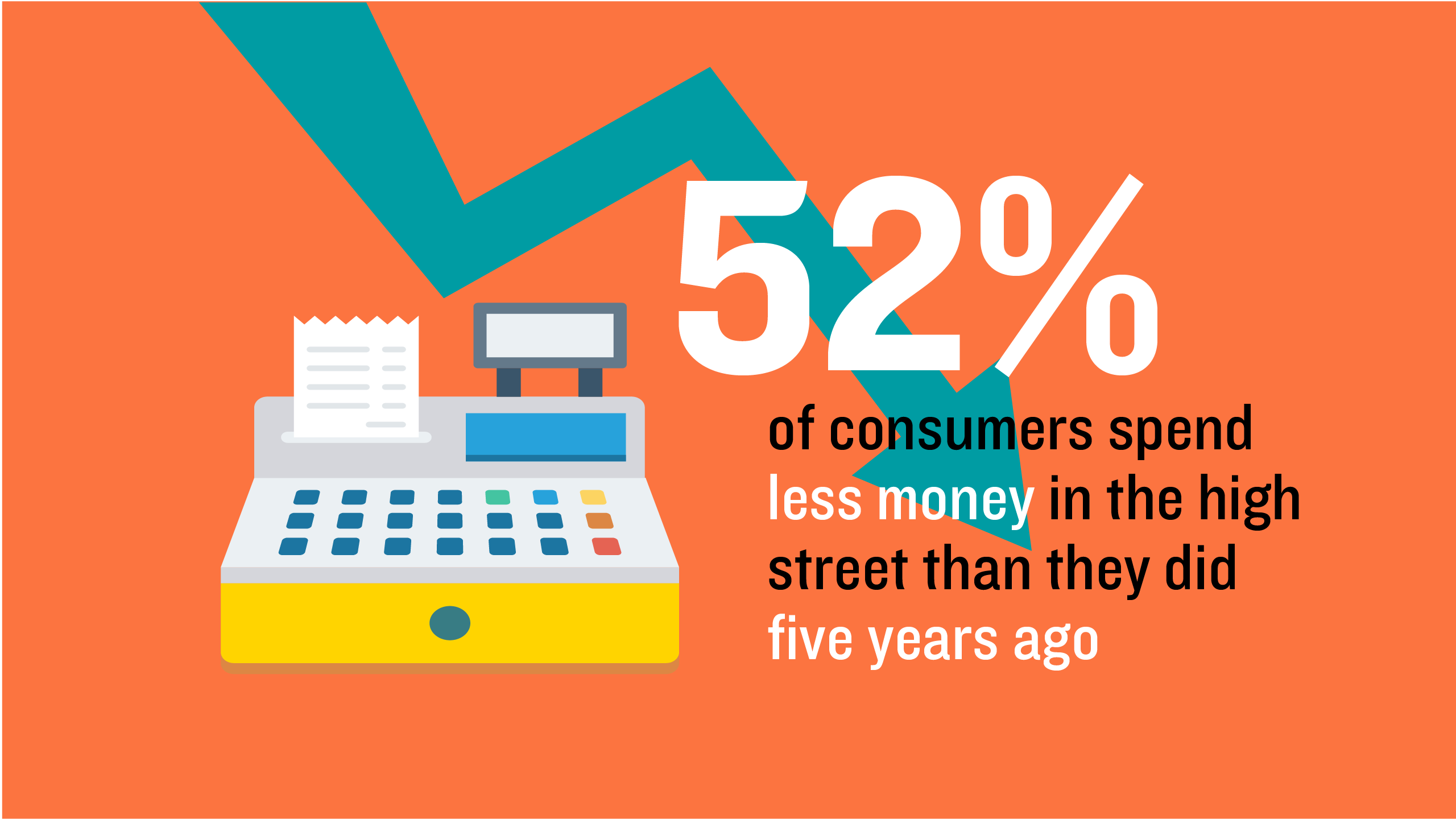

More than half (52%) of those surveyed now spend less money on their local high streets than they did five years ago, while half spend less time in these locations altogether. This suggests that fundamental changes are required to improve the fortunes of what was once the staple destination for British communities.

Consumers are getting used to seeing significant change in the type of businesses occupying high street units, as well as growing numbers of empty premises.

PwC is one of 13 partners in a consortium of organisations comprising the government-backed High Streets Task Force (HSTF). Its aim is to turn around high street fortunes and collate resources for communities to access to drive change across the UK.

HSTF executive director and co-chair of lead consortium partner the Institute of Place Management Simon Quin says the goal is to provide town centres and local authorities with access to experts in place management, as well as data and information, and guidance that can drive improvements at a local level.

“In the past high streets provided civic uses – healthcare, education and all that kind of thing – and we think that has got to be the future,” he says. “We are not going to be using a lot of our centres for multiple retailing per se.”

The rise of online retail and continued interest in out-of-town shopping are key factors in this – and are discussed throughout the report. Quin expects the big cities to specialise in hosting major brands and for smaller towns to become more independent-led.

Changing fortunes

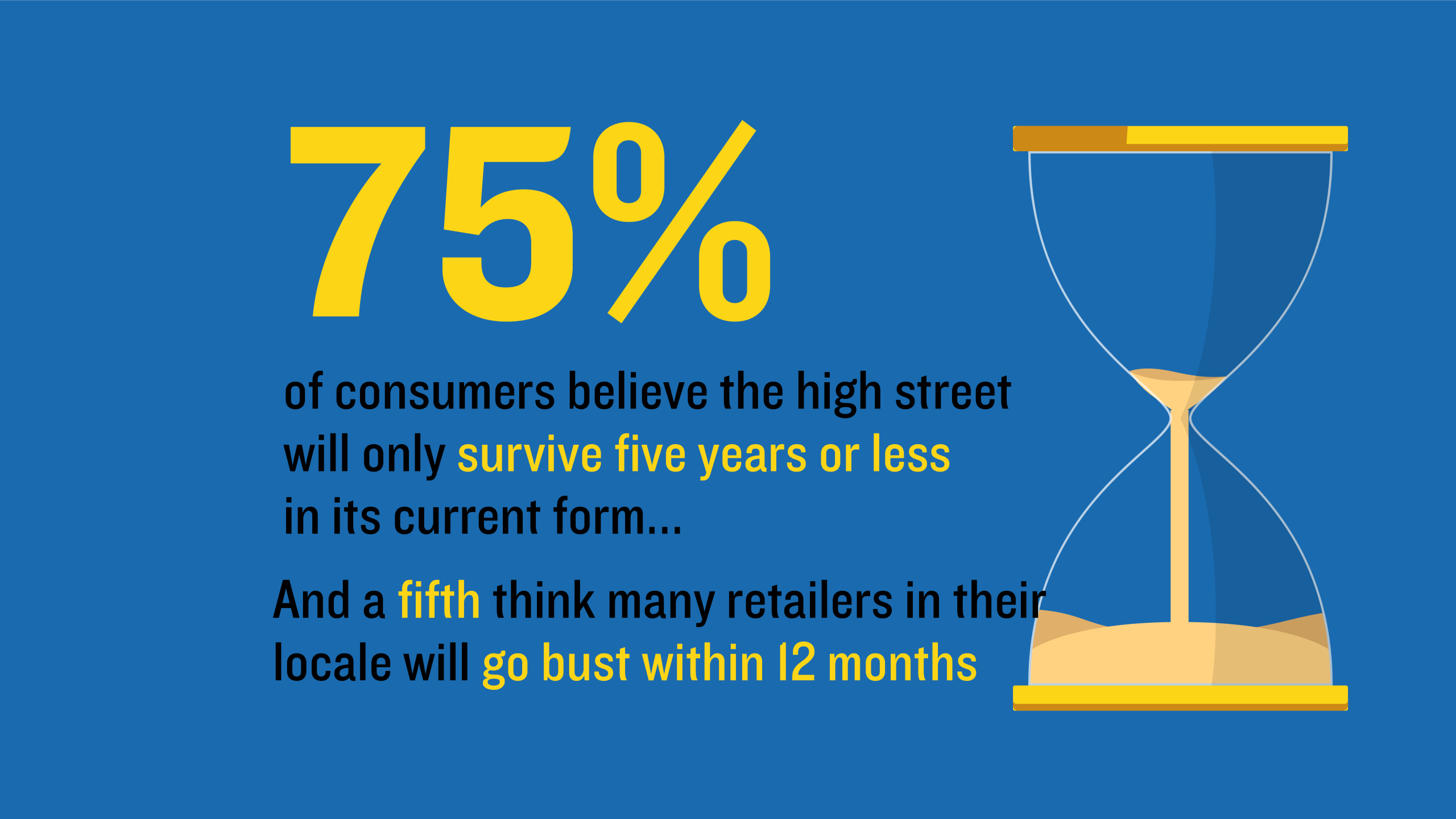

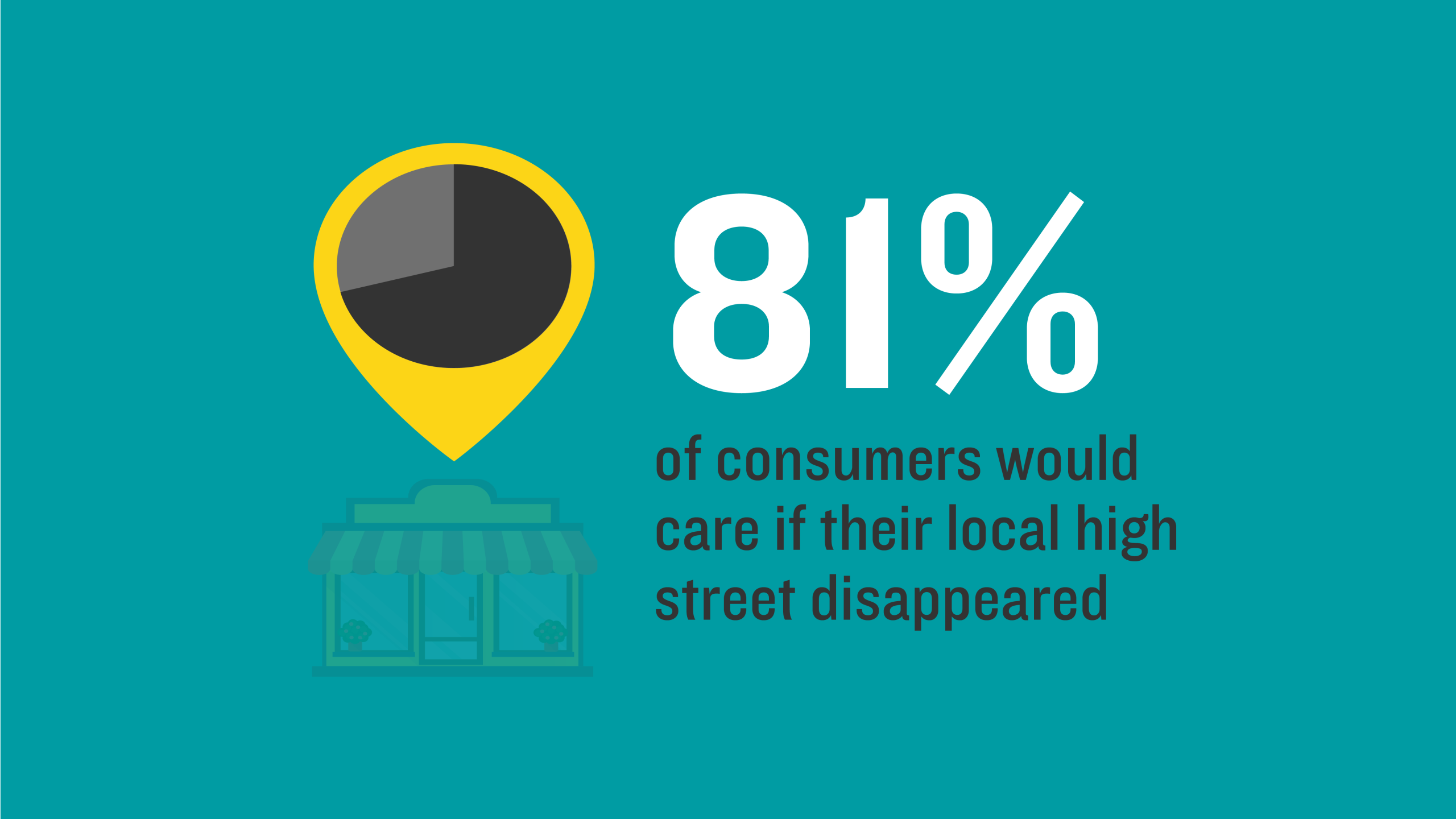

People are still attached to their high streets; 81% would care if their local high street disappeared. This figure is down by six percentage points, compared with the survey undertaken in 2019, but it shows that as retail locations high streets still have a strong emotional pull on consumers.

A third of people direct more than half of their high street retail spend towards grocery, but neighbouring service-led businesses, such as nail bars and hairdressers, are very much in demand.

However, each high street needs to develop in accordance with local demand and demographics. Our survey highlights both regional distinctions (high streets take a greater percentage of people’s spend in the West Midlands and Northern Ireland versus other areas), as well as generational differences (older consumers are more likely to direct more of their retail spend on their high streets).

Quin notes independent businesses are the key to characterising communities, in contrast to the ‘clone town’ model, popular 15 years ago when shoppers wanted access to global brands, but which is now becoming a thing of the past, perhaps made less relevant by ecommerce, as well as the desire for specialness. However, he says “it’s down to individual towns to decide what their characteristic is”.

For the high street concept to survive, it has to appeal to younger people. Under-34s are more likely to spend their money on health pursuits, fashion and entertainment than consumers aged 35 and upwards, our data shows. These are key drivers to securing thriving town centres in the future, as is ensuring the right infrastructure is in place for mobile-enabled consumers, such as free wifi and digital touchpoints.

One High Streets Task Force partner is The Teenage Market, an initiative engaging young creatives, performers and entrepreneurs to come together to make use of what would have been the traditional marketplaces in town centres. By creating them a space where they can contribute to a town's commercial offering, it encourages younger visitors and this type of pop-up concept is vital if high streets want to inject newness.

With consumers conducting most of their retail spend online via their mobile phones (26%), in shopping centres in town centres (20%) or online via desktop (16%) – the high street needs to look at where it is falling behind.

It should look to embed food, drink and entertainment options more appropriately into its proposition, similar to what shopping centres have been working towards, as well making the most of that all important USP – being able to host alternative experiences to online retail that supplement people’s increasingly digital lives, such as live performance, experiential retail and hospitality concepts.

There is also an argument that housing should play a greater role in high street locations in order to make them as integrated as possible into the spaces where people live.

Covid – the longer-term picture

Lockdown measures over the past year have weighed heavily in favour of online retail over ‘non-essential’ shops, with ONS data revealing online sales increased 46% from December 2019 to December 2020.

But what did the picture look like when all stores were permitted to open?

Almost two thirds (60%) of shoppers felt safe when able to visit high street stores in 2020 and 94% commended retailers for implementing the right safety procedures, the research shows. But with 43% having visited these locations less often since coronavirus took hold, there is work to do to draw people back once the mass-vaccination programme has been completed.

"Independent businesses are the key to characterising communities and it’s down to individual towns to decide what their characteristic is"

Several well-known retailers and hospitality companies, as well as independents, have struggled since the onset of the crisis, and this has accelerated the speed of change on the UK’s high streets, with more empty spaces appearing. It has been the death knell for already-up-against-it retailers, such as Debenhams and Arcadia, and seriously impacted trade and prompted store closures at previously soaring businesses, such as Pret A Manger.

“Some of our support is dedicated to individual [communities] and we’re working with the government to identify those places,” explains Quin, who admits the pandemic has slowed down the taskforce in its mission to present town centres, local authorities and business groups with the tools and expert advice required to revitalise their communities.

Early on in the pandemic the focus was on forming partnerships and dealing with immediate issues presented by enforced closures and the national lockdown, but that switched in the autumn to more long-term planning.

“Towns and their leaders need to think about transforming, and understand the future role of high streets is not retail dominated, but with many other things that occupy it,” Quin comments.

Chapter 2

What shoppers really want

Consumers’ eagerness to shop online over the high street may not simply be a matter of convenience and platform preference – it has a lot to do with the attractiveness of online players themselves.

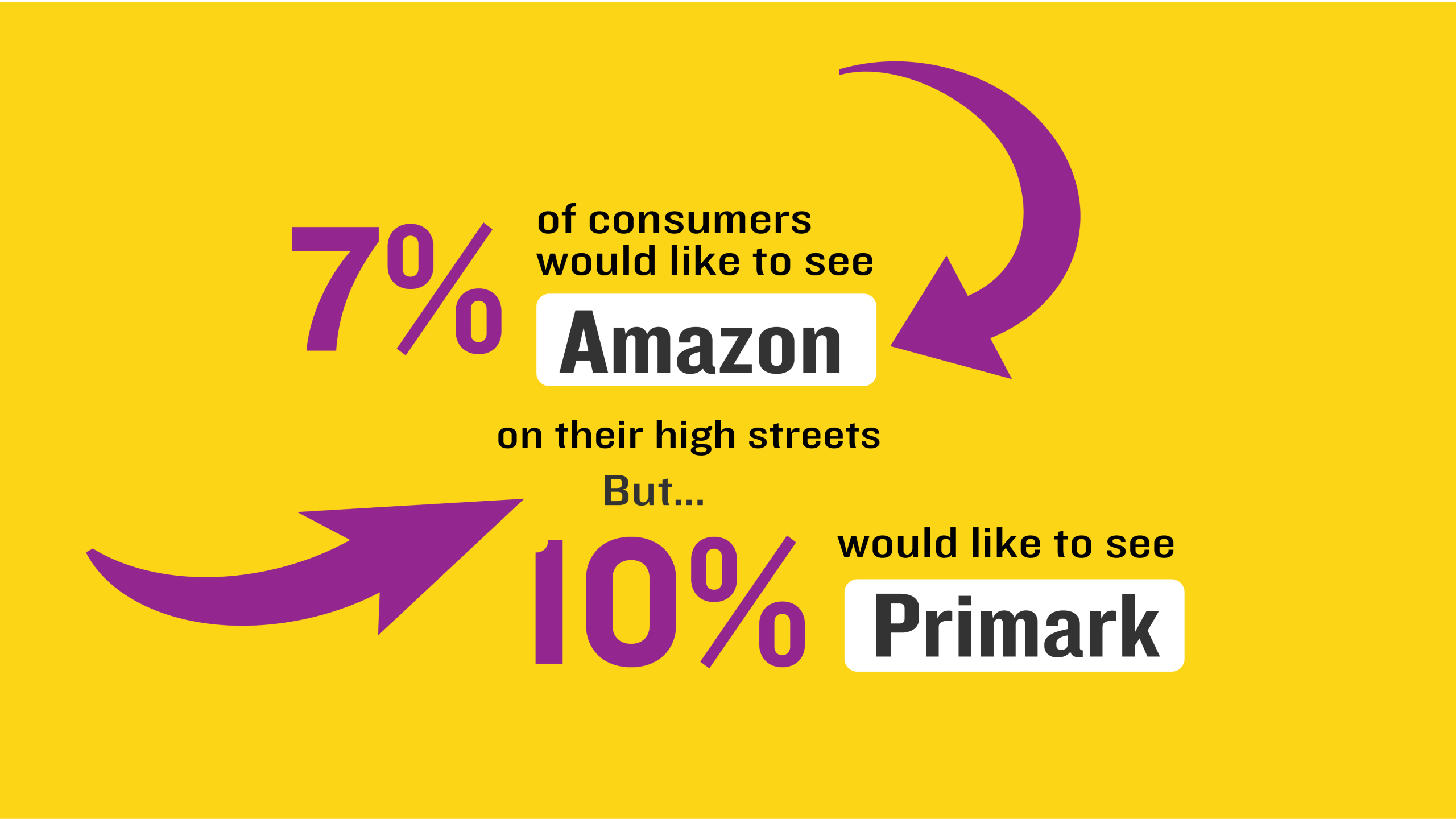

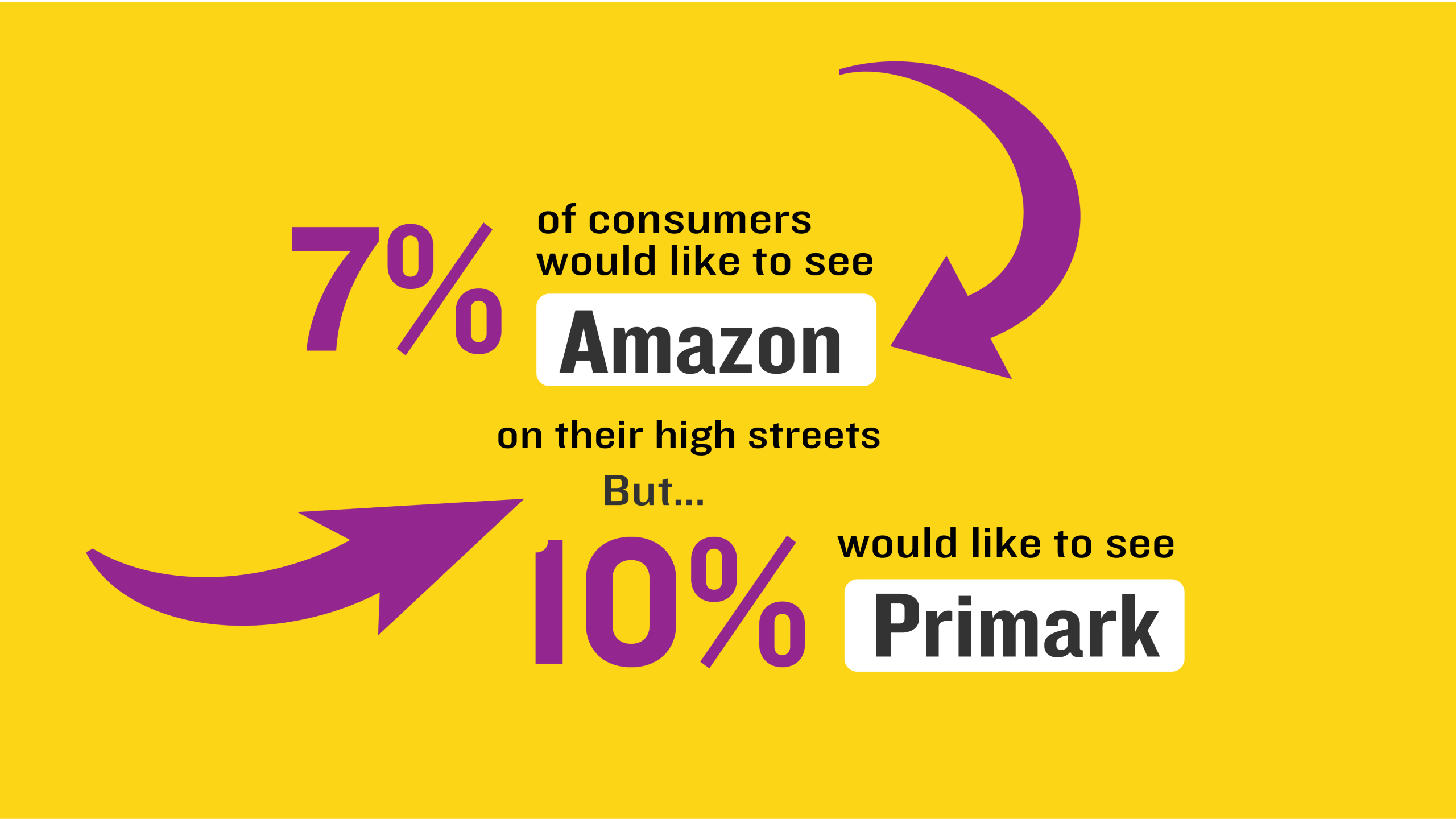

Some 7% of those surveyed by RWRC list Amazon as a retailer they would like to see on their local high street.

The digital behemoth has opened tech-enabled convenience stores and bookshops in US cities and is in talks to convert JC Penney stores into fulfilment centres. It is also known to be assessing its physical presence in the UK with speculation of different store formats opening.

Amazon owns upmarket grocer Whole Foods, which has seven physical stores in London, and it has also backed several independents in Manchester by supporting their pop-up stores, but its presence on the UK high street is really only in the form of pick-up and drop-off lockers at the moment.

Perhaps Amazon and successful online companies will fill vacant space and turn them into delivery hubs or create brand and customer relationship-building real estate. It’s all speculative for now, but our study shows there is demand for Amazon stores on the high street.

But our survey shows it is not all about the allure of ecommerce brands.

Primark does not have an ecommerce function and as a result, has estimated a loss of sales worth £1.05bn for its half-year expectations to February 27 due to enforced store closures during the pandemic.

Despite having 188 stores in the UK and a further 37 under the Penneys fascia in Ireland, 10% of consumers would like to see the value clothing chain on their high street, showing there is clearly scope for more.

Additionally, 3% of respondents would like to see the return of general merchandise giant Woolworths, which disappeared from high streets in 2008. Others suggest they would like to see a BHS comeback, which collapsed in 2016, with such nostalgia speaking volumes about the swingeing impact the disappearance of high street anchors must have had on consumers and their towns.

Footfall drivers

Additional grocery, fashion and entertainment retail shops, in particular, would make people visit their high streets more often, according to the research. These are staples of the traditional high street, suggesting consumers are looking for greater choice when it comes to the key retail sectors.

Amenities that consumers desire from their high street in 2021 include better/cheaper parking, coffee shops, restaurants or bars, and “a nicer environment” – as called for by a fifth of respondents.

In the commercial property sector, mixed-use development has been a key focus area for some time. This suggests those building future high streets are on the right path. However, the impact of overpriced parking on retail footfall is a long-term concern of traders in UK communities and clearly still needs addressing to encourage people to return.

Convenience and price are the main drivers for people to use their local high street, as was the case in the High Street Rebooted 2019 report. Like two years ago, the ability to try on clothes is also a key motivating factor for high street visits, suggesting online fashion retailers are still yet to solve issues with sizing and styling digitally. However, changing rooms have been closed during the pandemic and, with this likely to continue for the foreseeable future, retailers may find online tools a necessity for conversion when shoppers head in store.

A quarter of consumers feel motivated to use the high street in order to help their local community and 18% cite it as a location to meet and see other people.

It is therefore in multiple parties’ interests – businesses, civic leaders, consumer groups and developers – to work together to ensure local high streets can become a hub for the social prosperity and community spirit evidently desired.

Digital enablement

In addition to a nicer environment and more choice of retailers, consumers are keen for digitally enabled experiences on the high street. Some 56% are using self-checkout facilities in high street shops, but there is more demand for them – 22% say their high street does not offer them but would be very interested if they did.

There is a similar story with scan-and-go provision, where shoppers can use tech to scan products via a retail app and checkout. Some 34% are using these tools, but 26% say they don’t have the option on their high street, but would be keen to see it.

Many of these sought-after tech deployments are used by Amazon in the US and consumers in the UK evidently want to see it travel across the Atlantic. Not surprising considering the climate of health concerns surrounding coronavirus.

Several UK retailers do already offer systems and apps of this nature, including the major grocers, and sports retailers and brands such as Decathlon and Nike, but it would be prudent for more companies to explore the opportunities such technology brings.

Discounts matter

Perhaps unsurprisingly, considering the macroeconomic circumstances leading to widespread furloughs and redundancies, consumers are still keen bargain hunters.

Shops may have been quiet during the key Sale periods prior to Christmas, such as Black Friday, when consumers opted to shop online instead, but this year could look a lot different.

Across nearly every age group, our data shows consumers either ‘agree’ or ‘strongly agree’ with the statement ‘Why would I buy anything at full price when I can buy at a discount on Black Friday or another promotional event?'

Electricals appear to be a big motivator to wait for discounts. Only among over-65s does the percentage of shoppers saying they wait for key Sale days fall below 50%, and even then, the balance is still weighted in favour of ‘agree’ (see chart below).

Chapter 3

Location, location, location

A local approach that steers away from the homogenous commercial centres of yesteryear is going to be important for high streets to thrive. Specifically, our data shows that while national trends exist, there are significant differences between regions.

Out-of-town shopping

Out-of-town shopping centres take more of the monthly retail spend than high streets in Scotland and Wales, and in England’s East Midlands, Northwest and Northeast – these five parts of the UK are the only areas where this is the case.

For people living in these places, it appears Silverburn on Glasgow’s southside, Trafford Centre off the M60 near Manchester, and Metrocentre in Gateshead are more of a pull than their local row of shops close to home.

Out-of-town shopping is most popular in the Northeast, with 27% saying it is where the majority of their retail spend goes each month, compared with 14% on the high street; followed by the Northwest, where 16% of respondents spend most in out-of-town destinations, compared with 7% on the high street. The situation in the other areas is not as stark – Wales 13% out-of-town, 10% high street; East Midlands 11% out-of-town, 9% high street; Scotland 10% out-of-town, 7% high street.

With Metrocentre undergoing significant redevelopment in recent years and new retail concepts a regular occurrence – such as 2020’s launch of Next’s new beauty fascia and the arrival of a Hamley’s toy shop pop-up – the location pulls in people from across the region. Any high street in the area is competing with Metrocentre's mix of entertainment, recognisable names in hospitality and fresh brands, and will need to offer something that it cannot to attract the crowds.

Platinum mall, Metrocentre

Platinum mall, Metrocentre

Rather than taking a huge share of high street business, however, the popularity of Metrocentre and other sites like it among consumers in Newcastle, Sunderland, Middlesbrough and Durham is more to the detriment of ecommerce. The Northeast is the only region where out-of-town shopping centres are favoured more than shopping online via mobile and internet shopping in general.

The images that circulated nationally of hundreds queuing for Primark when it reopened its doors following the first coronavirus lockdown in 2020 underline physical retail’s importance to the centre and the region as a whole.

Meanwhile, with Oxford Street, Regent Street and Carnaby Street a mere few of London’s landmark shopping thoroughfares, it is unsurprising that 15% of consumers in the capital say the majority of their shopping each month is done in their favourite city-centre high street.

How much longer this is the case is a pertinent question, though, with Local Data Company figures from January showing 9.1% of space is vacant – with 24 of Oxford Street's 264 functional units standing empty. It illustrates that even some of the most renowned retail centres are undergoing serious challenges.

In terms of the biggest online shoppers, Yorkshire comes out on top. Some 48% of consumers in this region are more likely to spend the majority of their monthly shopping budget digitally, with Scotland, the East of England and Wales the next biggest online consumers. This suggests high streets have the most work to do in these areas.

Scots go green

High-profile stories about malpractice in retail supply chains, and a growing realisation of the impact the industry’s globalised operations have on the natural world have put retailers’ social and environmental credentials under the microscope.

With new generations of consumers taking these issues into account when choosing which retailers to spend with, it has become increasingly important for commercial reasons that these subjects are addressed. But once again, there are regional differences of opinion.

Environmental standards and focus on ethical trade has a significantly larger sway on Scottish consumers than it does on those in the rest of the UK, our research indicates. Some 20% of Scottish shoppers say they would be encouraged to shop at high street retailers if they make more of a commitment to sustainability, while 26% say knowing a retailer is ethical encourages them to shop there. This compares with just 15% of the UK as a whole.

The ‘made locally’ banner is also more important to Scottish consumers than other UK regions, with 21% saying locally manufactured ranges would encourage them to shop on the high street.

Such issues are much further down the priority list for those in the East and West Midlands, where low price and customer service, respectively, are more important than in the rest of the UK.

Independents and big brands

Shoppers in the East and West Midlands are most likely to be content with what they already have, with 18% and 15%, respectively, saying they don’t want to see any change to their high streets.

In terms of store investment or plans to radically change their high street proposition, retailers may be wise to conduct that elsewhere, in regions where there is stronger demand for something new.

Across the UK, 31% want to see more well-known names open up on their local high street to reinvigorate these areas, reflecting the disappearance of several long-standing retailers in the past few years.

Among retailers that traditionally had a strong high street presence but have closed significant numbers of stores – or been acquired and gone online-only – over the past five years include New Look, Karen Millen, Coast, Monsoon Accessorize and Beales.

With administration also befalling Arcadia and the decline of M&Co, Debenhams and Bonmarché, more familiar names can be lost to the high street. Boohoo and Asos are picking over the bones of some of these failed businesses, with the former already having acquired Debenhams, Burton, Wallis and Dorothy Perkins, and the latter taking on Topshop and Miss Selfridge. As online operators, the acquirers will not keep stores open.

Consumer demand for familiar names to reinvigorate high streets is most acute in Wales, with 40% of consumers surveyed calling for it, but it is also strongly felt by those in the Southwest and Northwest of England (both 37%).

As retailers disappear, the emerging brands replacing them such as Glossier, Ribble Cycles, Untuckit and Made.com – which were born online but are now increasing their physical footprint – are simply not opening as many outlets to compensate for all the closures, and they tend to opt for shopping centre or prime city locations.

Perhaps this is where independents can step in and fill the gap. The concept of our high streets comes from traditional market squares, where market traders drew people to their stalls, creating bustling hubs where people would not just shop, but gather together to greet each other and catch up on their news. That independent creative commercial spirit is required again.

A quarter of respondents across the UK would like to see their high street reinvigorated with independents, with this feeling strongest in Scotland (33%) and Southeast England (28%).

Black Friday influence

As we have discussed elsewhere in this report, low price is crucial in terms of getting people to spend their money on high street shopping. The UK is bargain-hungry.

However, there are plenty of examples of retailers building their strategies around optimising full-price sales and being careful not to offer too many in-season SKUs at markdown prices, including Fat Face and Superdry. Against the backdrop of consumers' low-price expectations, this will need to be done very methodically.

Retailers have taught shoppers they can buy most things at a discount in recent years – arguably stemming back to the post-financial crash period in 2008 – and that can be margin erosive. One oft-cited reason for consumers expecting a discount nowadays is the arrival on these shores of the American Black Friday sales events.

What started in the US as a post-Thanksgiving Sale day has morphed into an international event, stretching into a pre-peak period Cyber Weekend and – in many cases – a month-long period of discount Sales.

While Black Friday retail sales were down 16% in 2020, the discounting bonanza is still having a significant impact on shoppers and their willingness to part with their cash at other times of the year.

In our survey almost two thirds (64%) of consumers from across the UK agree with the statement ‘Why would I buy anything at full price when I can buy at a discount on Black Friday or another promotional event?’ This is particularly keenly felt in London and Northern Ireland, where 73% agree with the statement.

By category, electricals is where people are most likely to buy if a promotion is offered (46% of those surveyed). All UK regions ranked it as their top promotional purchase trigger category, while sports and leisure products and general merchandise were the least popular, giving an indication of where markdowns are typically most successful.

This is what retailers are up against when it comes to attracting people to buy their goods at full price. It is up to the most innovative thinkers in the industry to develop new ideas and concepts to supersede this shopping mentality.

Give and take

There was no real rush to the high street overall in 2020, as our research and that of the ONS indicates.

Although 18% of our survey respondents say they visited their local high street more frequently in non-lockdown periods since the coronavirus crisis started, 43% say they visited less often.

Despite some positive individual examples, overall decline in consumer traffic is a continuation of a long-term trend. As referenced earlier, 50% of consumers spend less time on their local high street than they did five years ago; double the figure reported two years ago in High Street Rebooted 2019.

Retailers and communities need to ask themselves how to make the pandemic the nadir when it comes to high street footfall levels. They need to start moving things in a more positive direction and changing the function of the high street.

This is discussed fully in Chapter 4, but as a starting point it would seem prudent to recognise pandemic trends.

Retailers such as Majestic Wine and Co-op ramped up their online services, using stores in the heart of communities as hubs for ecommerce picking, packing and fulfilment. The convenience sector was providing 600,000 home deliveries a week in September 2020 – a figure multiple times higher than at the start of 2020, when few stores of that type were digitally enabled, the trade body Association of Convenience store reports.

While these examples of embracing digital and merging it neatly with physical shopping are cases of ‘if customers won’t visit us, we’ll visit them’, there are other tactics retailers are using to actually draw shoppers into high streets.

The Body Shop has offered call-and-collect services for some time, but last year saw several other retailers amend their fulfilment processes to ensure they could continue to trade in the crisis.

Co-op introduced an order-by-phone service for customers not able or not comfortable with online shopping

Co-op introduced an order-by-phone service for customers not able or not comfortable with online shopping

The White Company launched a call-and-collect service, allowing consumers to phone in an order and collect it within a matter of hours. Central England Co-op also offered this service, acknowledging some of its local shoppers did not want to go out to get in food supplies, but also were not able or comfortable with online ordering systems.

This type of localised flexible service can help retailers get to know their customers, and is a light-touch traffic driver offering convenience.

Chapter 4

What this means for the high street and where to invest

Some 59% of shoppers across the UK say they feel compelled to support their high street. It is mainly for economic and social reasons, with 29% saying they want to support local businesses. A quarter believe it is good for the community and 23% say it’s because they want to support local jobs.

However, as previous responses have shown, these sentiments do not necessarily result in people actually supporting their high streets. As ever with consumers, there is a dichotomy in what they say and what actions they take.

PwC management consultant Evelyn John acknowledges there is a gap to be filled. “If a consumer can’t fulfil their needs where they want to, then they won’t,” she says. “ It’s a challenge for anyone interested in revitalising and regenerating the high street.”

Turning the debate on its head, and asking why consumers don’t feel compelled to use their high streets, is perhaps more useful. More than a quarter (26%) say the fact they can shop elsewhere, namely online, means they don’t have to go to the high street.

Difficult and expensive parking (for 22%), narrow product offerings (for 14%), and unappealing and outdated shops (for 14%) are the main issues putting them off.

HSTF’s Quin says it is up to community members, businesses, local enterprise partnerships and business improvement districts (BIDs) to work together to solve these issues, and pave the way for thriving high streets.

“That process of rethinking a town has to involve all of the community, businesses, transport operators, et al,” he explains, adding that the task force has built a “route map for transformation” based on guidance from its 13-strong consortium of experts, which includes the Royal Town Planning Institute, the Landscape Institute, the Design Council and the Association of Town and City Management.

Quin suggests local authority cuts over the years have meant officers who understood regional needs have been lost, and he argues BIDs alone were not strategically focused enough to work towards a comprehensive future vision.

"Every high street has a different starting point, therefore your response is reliant on having that leadership capability, not necessarily the set of things you do"

John says there is reason for positivity because local communities are starting to appoint designated leaders to drive change and start mapping out the future for their individual places.

“Every high street has a different starting point, therefore your response is reliant on having that leadership capability," she explains.

What the retailers say...

Louise Hoste

Spar UK managing director

“Everyone has a part to play – the government needs to make it a fair place for us all to trade; retailers need to make it innovative and give customers what they want; and customers have to think about the dynamics of the market and actually understand it’s a big part of the UK economy,” she argues.

Whether it is enabling smaller stores to be more innovative, or facilitating big chains to be profitable on the high street, Hoste says it is within “all of our remit” to find the right format for high streets.

“The pandemic has made us realise how fragile the model is if we’re not careful, so we all have a part to play in recreating the model or morph the model to enable the economy to spin.”

Mintel research predicts UK convenience sales growth of 8% in 2020, compared with the 3% growth achieved in 2019. Association of Convenience Stores data indicates the convenience sector generated £44.7bn in 2020.

Hoste predicts that online and home delivery or pre-order collection services from high street stores, which have multiplied during the crisis, will remain. But they should be there to provide alternative shopping options, not to replace traditional retail.

Stores themselves should be “exciting, innovative, friendly and community based to ensure people carry on going there”, she says.

John Colley

Majestic Wine executive chair and chief executive

“Shops need to be different – experienced-based retail format, and/or differentiated service and product; a place consumers are prepared to visit,” he explains.

“At Majestic, that means expert staff, exceptional range and first-class advice with free tastings – something that is extremely hard to replicate online.”

Colley also suggests retail needs support from property owners and local councils.

“We're currently looking to open new branches across the UK, for instance, and it's extremely difficult sometimes. This can be because of landlord demands or for other planning reasons.”

Colley says Majestic successfully opened a store just before Christmas in Henley-on-Thames, Oxfordshire, thanks in part to co-operation from the local community and the “right conditions and support”.

“Unfortunately, that isn't always the case and some locations are proving extremely challenging,” he adds.

Majestic says revenues more than quadrupled during spring 2020, as consumers drank more at home while bars, pubs and clubs were closed to the public. And while Colley notes that the shift to online, combined with the pandemic, has had a huge impact on high street retail, he is still positive about the future of the high street as a retail location, especially as footfall returned when stores opened in between lockdowns.

“There can be no resting on your laurels, or just opening the door and expecting people to come back in,” he warns. “We need to keep providing an experience and service which is fundamentally compelling. Consumers are inherently a social species, and people love experiences and communicating about great products face to face. And backed up by other services which add the convenience element or that special difference, there will always be a future for that.”

Peter Williams

Superdry outgoing chairman and ex-Selfridges chief executive

“The fixed cost base for physical shops is being helped to a degree by landlords being more realistic, but permanent and material reductions in local taxes may never happen.

“Therefore, for the economics to work for a particular store, the onus is on the retailer to provide a reason for people to visit; otherwise the store will die.

“There has to be a brand experience because, unless you are trading on price and/or convenience, what’s the point in going to the store?

“On ‘planet fashion’, significant emphasis is placed on great product and design, and rightly so, but how often is that negated by an unexciting store, a grotty location, poor customer service and insufficient integration between offline and online?”

Williams acknowledges customers have realised they don’t need shops in quite the same way as they used to, partly owing to the advent of online, and he says that the pandemic will have changed shoppers’ psyche in regard to physical shopping trips.

“It’s up to the retailers to convince them otherwise,” he adds.

Louise Hoste

Louise Hoste

John Colley

John Colley

Peter Williams

Peter Williams

Chapter 5

Strategy distilled

Five steps to save stores and reboot high streets

Localise

There is no template for how a high street should look. Gone are the days of clone towns; a thriving town centre needs to develop its own character, drawing on all areas of the community to create a space local people want to visit and a broad range of businesses and service providers want to invest in.

Revitalise

The decline of the high street is not something that has happened overnight. Though problematic for businesses and communities in multiple ways, the pandemic itself is not the underlying cause of town centre deterioration, although it has certainly added to store and brand closures. What it has highlighted is that all stakeholders need to think differently about what they want their high streets to be and need to bring joined-up creative ideas to the table.

Digitalise

Despite the advent of digital communication, ecommerce and online entertainment – which sped up in 2020 – consumers don’t want to spend their lives in front of a screen. But they do need their high streets to be more digitised – whether that’s shops that offer online collection, self-service tech or free Wi-Fi. Local centres must embrace people’s digital behaviours rather than pretend they don’t exist, and that will harmonise the on and offline worlds.

Differentiate

If more people now shop in out-of-town centres and online, compared with the high street, then those responsible for the latter must focus on delivering what these destinations cannot. It might be offering vibrant market spaces, a commitment to the arts, independent retailers, or more amenities around education and health, or on an individual company basis, it could be greater personalised shopping concierge or more compelling brand experiences.

Collaborate

Delivering high street prosperity is not the responsibility of one type of business, organisation or authority; it’s a team effort that absolutely requires a group of stakeholders all working creatively in tandem, using an evidence-based approach to strategy, to deliver what is most suitable to their individual community.

Partner messages

Ben Gale, regional vice-president and managing director EMEA retail sales management, Diebold Nixdorf

Retail is always evolving, but the past year has had a tremendous impact on how consumers shop. Not only has consumer behaviour changed, but end-to-end consumer journeys have completely evolved. Having a self-service option that provides a low-touch or even no-touch shopping experience is becoming expected. This optimises in-store shopping by removing friction as much as possible and, in the end, also lowers the total cost of ownership for retailers.

A recent study of more than 15,000 grocery shoppers, carried out by Nielsen and commissioned by Diebold Nixdorf, found a steep increase in consumers preferring smaller basket sizes and higher shopping frequencies, supported by fast, convenient and low-touch in-store services. According to Nielsen, 48% of Gen Z and millennial shoppers do their shopping several times per week, compared with 38% of Gen X and baby boomers. Despite Covid-19, going to physical stores remains the preferred option for most consumers.

As adoption levels of self-service continue to rise, agile high street retailers are investing in new types of consumer journeys like self-checkout and mobile self-scanning using either retailer-owned hand-held scanning devices or consumers’ own smartphones. This reduces physical interactions between consumers and staff, and overall time waiting in queues. According to Nielsen, waiting in a queue is the number-one frustration for shoppers (37% of respondents) and self-scanning items to enable them to leave the store faster would solve that friction point.

Self-service options empower consumers to choose the shopping journey they prefer; one that’s intuitive, frictionless and at their own pace, whether in grocery stores, malls, fashion outlets, convenience stores or at fuel stations. With the clear separation between online and offline shopping channels disappearing, connected experiences with consumers in control of their shopping journeys will be the new norm.

After a year of uncertainty that was unlike anything the UK’s high streets have ever experienced, we see much success for retailers that invest in their future to create meaningful shopping journeys in this ever-changing environment.

Love this report? Why not book in one of our experts to present the findings to your team, examining what they mean for you and your business. Contact Isobel Chillman at isobel.chillman@ascential.com

High Street Rebooted 2021

Written by Ben Sillitoe

Produced by James Knowles, Rachel Horner, Stephen Eddie, Rebecca Dyer and Helen Berry

In partnership with Diebold Nixdorf